Editing: The Other Half of a Photo

A few—okay, more than a few—of my thoughts on editing, my process, and why I love photography in general. I wanted to take a lot of the things I have been asked over the years and compile them into one place. This way, if someone really wants to know, it is all out there. While I try to keep these thoughts in chronological order as much as possible, you will feel some time shifts as I reference past and present ideologies.

Immortalizing a moment with the press of a button

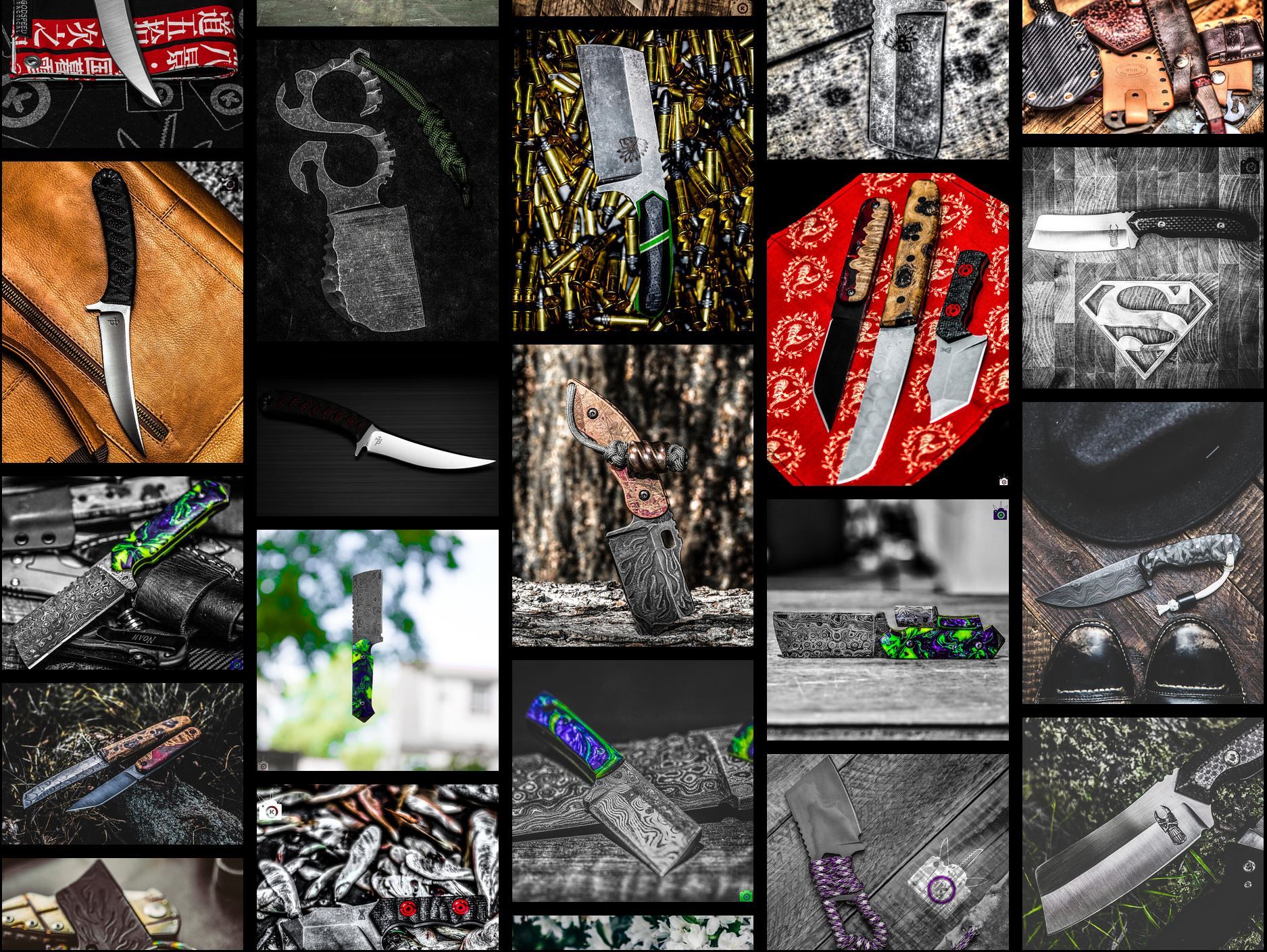

Before I go back in time, I feel it is important to state my philosophy on photography as it stands today, and why editing is so important to me. I capture a lot of still life. Things, yes, but it is not so simple. Most of what I capture are works of art in their own right. When I put something in front of my camera, the intent is to show people who come across my work every moment the creator puts into their work. This started with custom knives. Hours upon hours are put into them from the design phase, to forging, to finishing. I know I cannot capture every second of that with one press of a button, but I will certainly give every effort. After that, refining every last bit of detail in lighting, color, texture, mood, and tone is more than just important to me, it is a therapeutic creative outlet.

When you edit a photo, you can choose whatever fits your vision. From true to life, to a more creative touch, you as the photographer interpret what was in front of your eyes. I remember having this discussion with a friend when he first started out in photography. His philosophy was that editing was tainting the photo, but after showing him a few edits of his own work, he began to realize he did the same thing as I did when starting out. Thinking a photo is finished the moment you press release the shutter. As we both learned, that is merely the beginning.

It all started with Lightroo—wait, no Picasa!

When I first got into photography, it was digital. I only knew of “what you see is what you get.” Editing was not completely foreign to me, but I shot in JPG and the result was fine. It was only after I was looking for a way to organize my digital photos that I thought about editing.

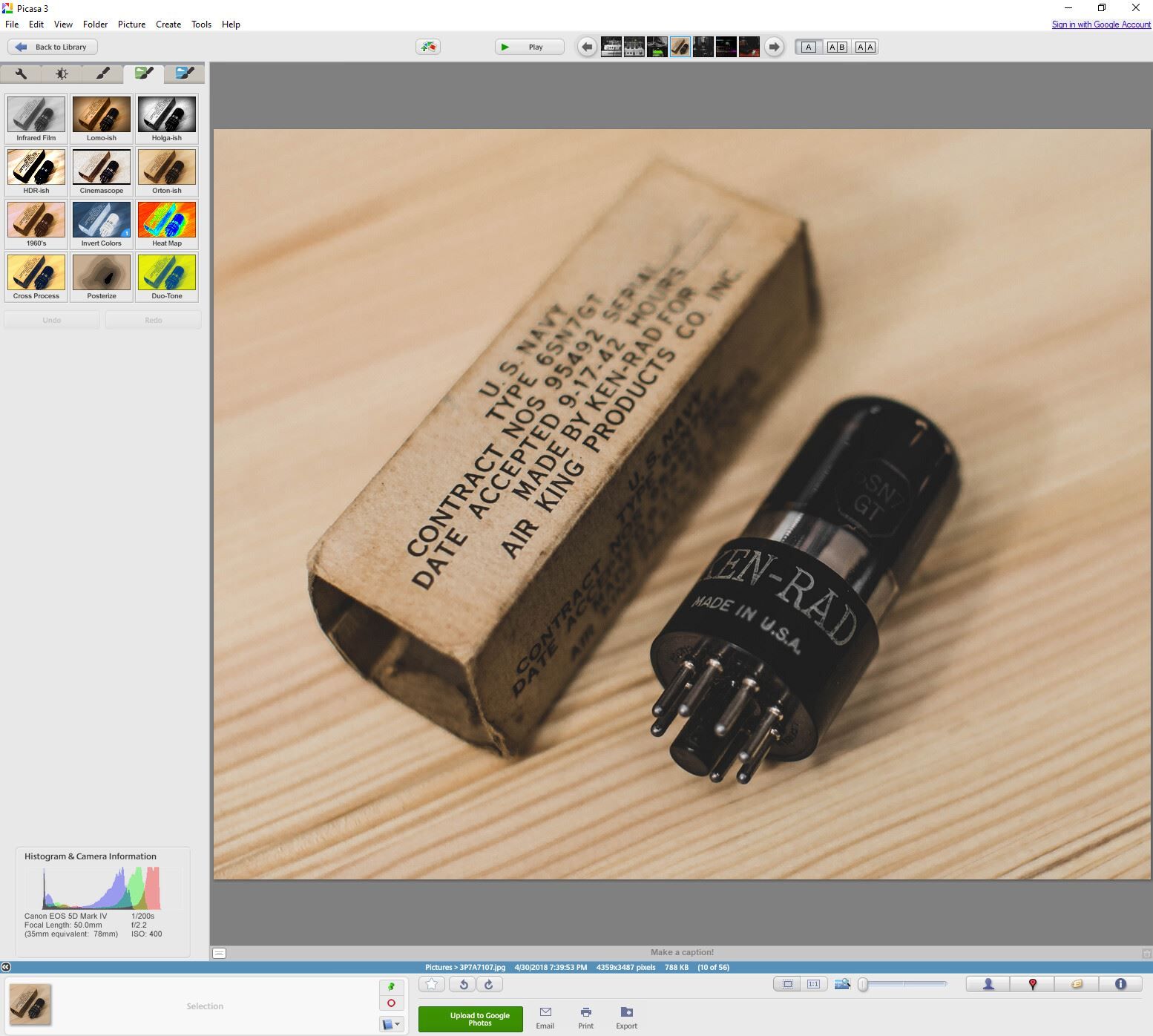

I will not lie. I take shortcuts. Often. I installed a trial of Lightroom after understanding it to be a necessity. Opened it, imported a batch of photos, saw a whole bunch of sliders and options then closed it… and downloaded Picasa. If all the people I have lectured into using Lightroom over the years discovered that this is how I started off, they would never let me hear the end of it.

It is not a case of finding Lightroom too difficult to use, it was more because school and work had a total monopoly over my time. Picasa found all my photos, pulled them into a neat place, and let me make minor edits here and there. It was enough. Cropping, straightening, geotagging, and emailing were features I used often. Occasionally I would need to use the red eye tool, but it was very rare. Picasa made destructive edits but made sure to preserve the originals in a separate folder. A lot of the “effects” were tacky and generic. I never saw the appeal of most. Sepia, film grain, and tint are things I would be more likely to try to fix than to apply on purpose. Soft focus added a bokeh-like effect, but you could always tell when it was used—abused.

I had a good run with Picasa, I really did. Once the pressures of life subsided, I wanted to know more of what my camera could do. I never research first when it comes to more personal projects. I prefer diving into it, making mistakes, then consulting documentation when I hit a brick wall. When I moved from my Canon Rebel XTi to a 5D, I knew I could not continue to shoot JPG. I switched to RAW. Upon importing to Picasa, I was greeted with highlighter green and fluorescent pink images with details so blown out, that you could not tell what the photo was. The first thing I did was check for an update. The update installed without incident, and the changelog revealed that Picasa was now compatible with CR2 RAWs. Great! Great? No. RAW handling was unbelievably slow in Picasa. Attempting to zoom in on a photo would lead to programs crashing most of the time. I could not deal with this.

Exposure to the light – Room for growth

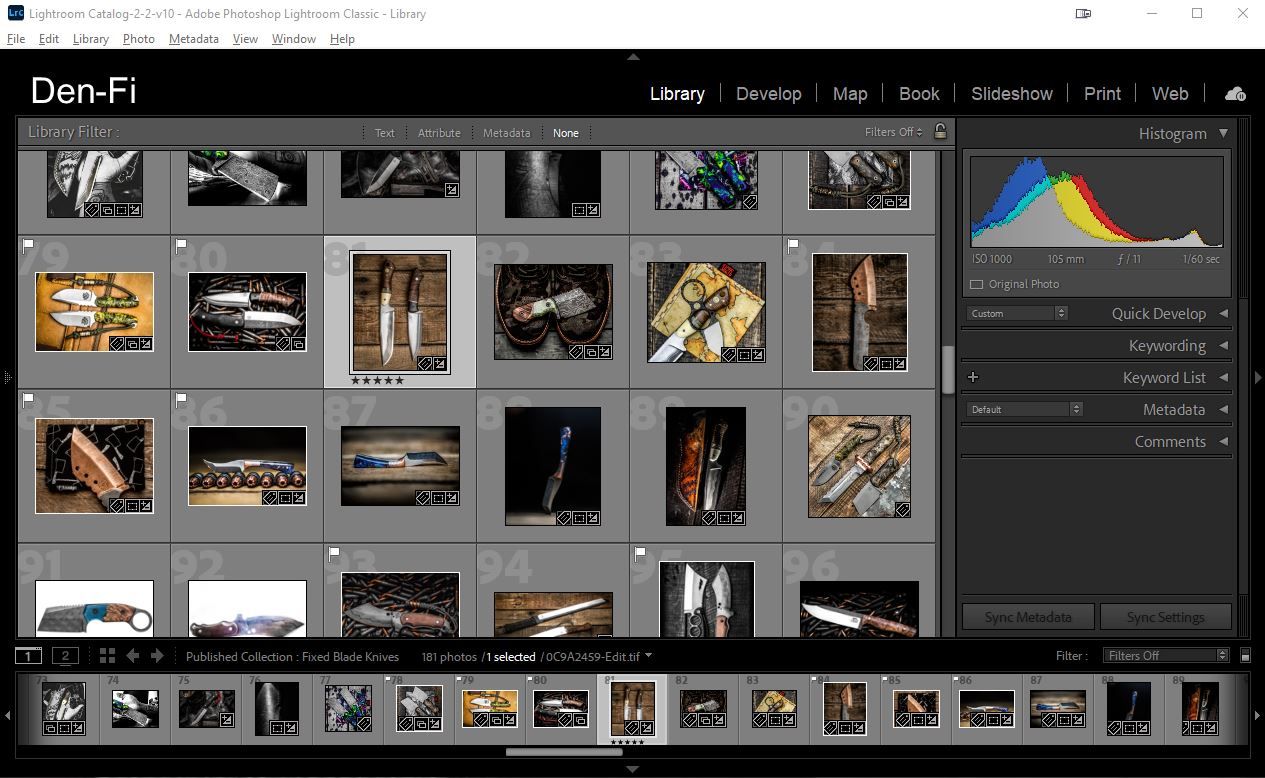

My trial of Lightroom ended, but it was a beta. This meant downloading Lightroom again would get me another 30 days. Great. I installed Lightroom, set up a library, imported all my photos, and spent some time poking around. This time, with a clearer head, it was not overwhelming. The workflow and layout were common sense. The one thing I did not get initially were presets. Given I just came from Picasa, it did not occur to me that I could make fine adjustments to the presets, so I did not use them. Instead, I just became very familiar with the sliders and their roles. This turned out to be just fine, since even when I did learn to adjust the included presets, I did not like using any of them as a base.

I still used Picasa for geotagging more personal pics that did not require editing, and it was amusing how primitive the program now felt. That said, there were notable admissions from Lightroom. Geotagging, web connected albums, and reliable emailing to name a few. Lightroom could email, but the feature broke so often that I stopped relying on it. Collages were one area of Picasa that was only replaced recently with Adobe Spark post. It's a web app, and not built into Lightroom, but at least I can use it now. It is a far cry from Picasa's built in collage maker, but it is a different tool for the most part.

Like many Google products, Picasa started growing in ways I did not like. One update included what had to be the most annoying photo viewer I have ever come across. It made several attempts at being modern but did so at the expense of usability. It would open photos in full screen, requiring many clicks to do the most basic task. I removed it immediately. The portion of Picasa that watched for photos started going haywire after a while, often claiming it discovered tens of thousands of photos that were already indexed. Perhaps I had too many photos for it (at over 120,000), but I could feel its usefulness diminishing each time I used it as I learned more and more things Lightroom could do. After leaving Picasa behind, Google did the same. They found a new toy in 2015, releasing Google Photos. Google Photos is a web-based product. Google’s bread and butter. Google Web albums existed for a long time, but now everything would be merged and the excess—Picasa—killed off. It was sad hearing the news. You never forget who helped you in the beginning. I will always have fond memories when thinking back.

Style – The early days of clarity?

For the purposes of this piece, I will only talk about my editing styles for inanimate objects. When I shoot fashion and other people related projects, they often use in-house editors, or I edit based on the style of the client/model.

As I said earlier, I started with custom knives as still life subjects. Most of what I changed about an image was mood/tone related. I lit the knives at first with constant lighting blasted at the ceiling for diffusion, before shifting to a single Canon 430EX Speedlite bounced from the ceiling. I did not care much for accuracy or noise. I cared about texture. To a fault. I feel I did what most people do when they first learn Lightroom. I found the clarity slider and became infatuated with it. When I look back at my earlier work, I can almost hear myself screaming MORE! I will save you from having to read more with a ton of exaggerated O’s but know that I should have used about 20. Really. I just went crazy with it. So much noise. So many harsh shadows, but you know what? I was putting forth my vision, and people were enjoying that vision. I do not regret having that as a starting point.

Insta gratification – Filtered frustrations

Instagram was the stage for my knife photography. It is how I discovered knives, and many other custom items, in the first place. It is also where I picked up a lot of bad habits. I was never into filters but did start to incorporate some of their characteristics into my editing style. One of the things about Instagram is that you are taking thousands upon thousands of pixels and editing them down to a phone screen that tops out at 6-7 inches. You start to exaggerate things that you normally would not on larger screens. Instagram permanently ruined HDR photography for me, and I suspect it did the same for many others. Those poor, poor pixels. This is likely the cause of my clarity slider infatuation in the beginning. It was not until people started asking me for prints that I noticed the devastating effects. Another habit I picked up from the Instagram scene was the “fade” effect or boosting shadows and black levels. I generally like the matte look. It has a calming, mood setting effect. I still use it, just in extreme moderation.

I owe a lot to Instagram. That was really the first place that taught me to use photography as both an outlet and a way to speak to others about things I enjoy. Some of my most cherished connections and interactions are because it existed. Then Facebook bought it. Algorithms took over. You had to play games to be seen, then more games once the algorithm adapted. It was a chore. You were shown what they wanted you to see, then told “we’re showing you what’s important to you.” Creativity was crushed in favor becoming viral. It is in a sad, sad state. It is more a video and shopping platform now. I can hardly find motivation to post. Everything has that signature Facebook homogenization. You go there to sell, be sold to, or be sold. A much more soulless end than what happened to Picasa.

Highly selective – Not for everyone, but certainly for me

One element of my style that has never changed is my propensity to selectively color an image. I enjoy isolating and highlighting specific colors. Especially in predominantly black and white images. Pops of color are visually appealing to me. I tend to focus a little less on that these days. My modern rendition of selective coloring is working around the minor limitations of not setting up a “proper” studio in home. This often leads to the yellowing of things that should either be black, white, or a shade of gray. So now, I will just carefully remove that via layering. I love the result this produces. I do find that it confuses some, but I cannot see it ever being something I stop doing.

For more specific things like contrast, shadows, highlights, I do have a formula, but it tends to be like being asked to show your work with simple math. I can no longer explain the exact science. I purposely shoot underexposed since it is easy to recover shadows from a RAW image. Trying to recover detail from a blown out image is near impossible. In that regard, I never shoot for perfect exposure in camera. Under is a much safer bet.

Editing is not magic. There are a lot of things you need to get right in camera. Composition and lighting can be slightly tuned with cropping and light adjustments but, planning to do all of that in post is not going to get you very far. Make certain you have a clear vision of what you want before you start. As for lighting, I use a single AD200 Pro bounced from the ceiling when I shoot at home. I modify the light with a Flash Bender and will sometimes use translucent diffusers depending on the situation. If you are just starting out, natural or constant light may be a better idea until you get used to using strobes.

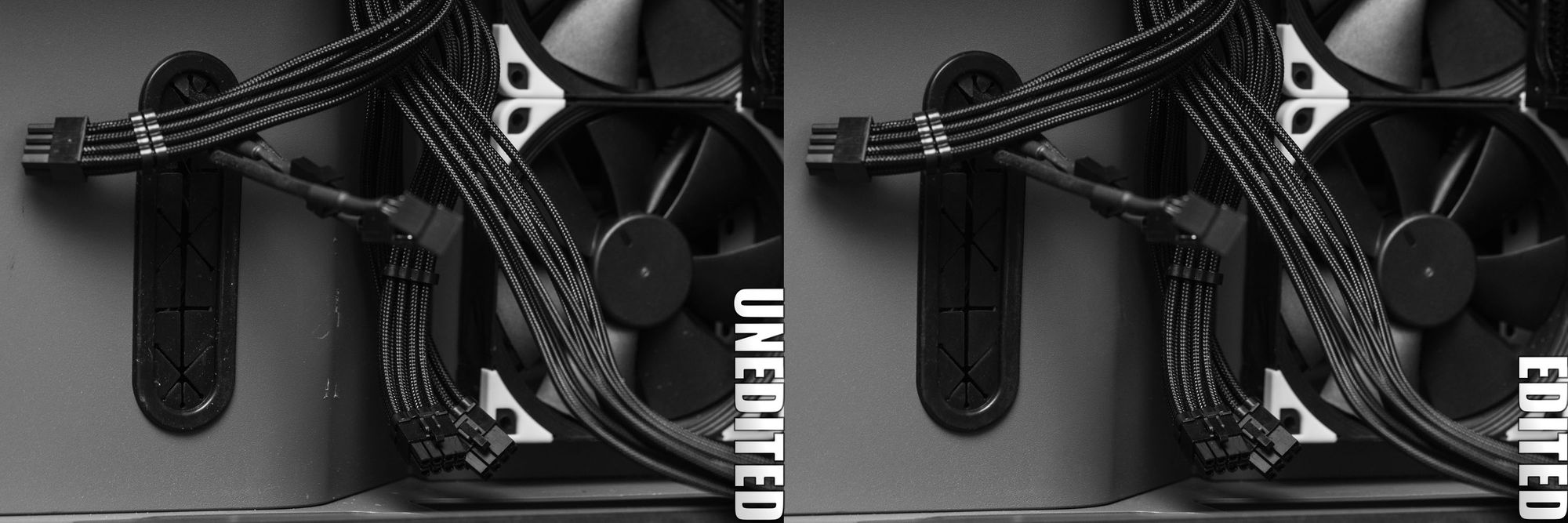

Fixing flaws – Corrective edits

Macro photography is very revealing. You get so close to the subject, that you see things the naked eye would not. One of those things happens to be my biggest pet peeve. Dust. No matter how tidy you keep your set pieces, no matter how much you dust, no matter how much you think you cleaned the subject to perfection, the macro lens sees all. It is an unforgiving, merciless, heartless tool.

You set up a shot. Release the shutter. Review it quickly in the viewfinder. You nailed it! Heck yeah. Then you import it into Lightroom. Like giant boulders of shame, massive pieces of dust actively tear down the house of confidence you built earlier. All your preparations, hopes, and dreams for the shot were for nothing. Why did you even try? Just hang it up. Sell your camera. Let it go to someone who can skillfully use it to produce a decent image.

What was that?! Sorry. That is just some of the dialog I have with myself when, despite all my OCD fueled effort, there is dust in the shot. There is nothing you can do about it. Dust exists. Seen, unseen… all we can do is reduce the amount of editing that is needed when shooting macro outside of a quarter million-dollar, oxygen-free clean room. There are other unavoidable situations when shooting things you use every day. Brushed finishes on knives that attract fingerprints, yokes of headphones that pick up dust/hair in the corners, or debris from tightening a water cooling fitting so that it does not leak. These are part of life that will spill into the shot. When I make corrective edits, it is to deal with something that is my fault. I use the things I buy, so if it shows signs of wear, I tend to edit that out (if it is something cleaning will not resolve). I never want someone to assume that this is how it comes from the creator.

A consistent style is one that always changes

Occasionally, I will see an older photo I took that I actually like. It sounds like I am saying I never take photos that I like. Yeah, I am. I tend to be my greatest critic. Mind you, I do not feel disdain for my own work, it just has a similar effect to hearing your own voice. Having said that, I will look at an older photo, like something about the photo, but the edit leaves me feeling like I had no idea what I was doing. I do not count this as a bad feeling. It often comes out as “hey, that guy was onto something! Time to finish this.” It is a great feeling because—this being my 3rd piece about a journey—I enjoy exploration. Exploration of myself most of all.

One of the best things about Lightroom is that it is a catalog of changes. You can go back and basically get a timeline of your thought process, one of the greatest things I never realized would be so useful to me (on a personal level) when I started using Lightroom. I take note of what I did to the photo originally, make a copy of the photo, then reset it. From there, I edit the photo with my current style and then compare the two. It is always very interesting that there is never a night and day difference, but it feels like it. Almost like having a conversation with my past self, it really helps me grasp who I am today. Even if it reveals that my OCD has gotten a lot worse.

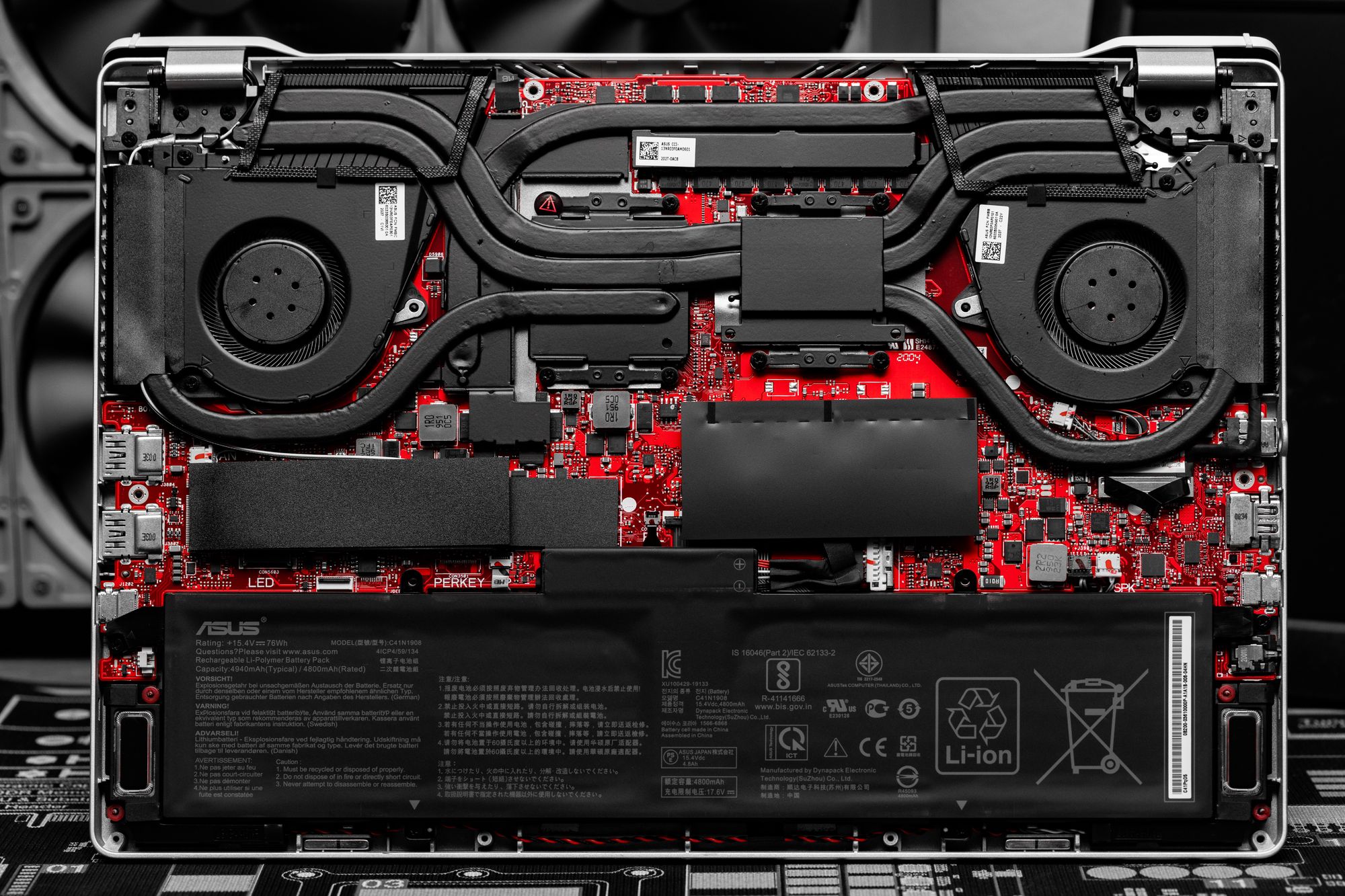

The changes in my style focus on ways to let the creator of the piece I am photographing know that I appreciate it. That knife maker that spent a few extra hours on hand polishing. The person that designed the internals of their keyboard for me with small details only I would see when assembling that keyboard. The PCB designers at Apple make sure I know that they were proud of their PCB, even if most people never get to see it. So, when I get something, no matter how small it is, I photograph it. I appreciate it. I try to capture it in a way that will make others appreciate it too.

And now, a few thoughts that do not fit neatly into the subject of editing, but I feel the need to get off my chest

Pocket Powerhouses – Computational photography… is not for me

I am often asked if I am impressed with what phones can do. And I am. Just not impressed enough for my use case. Like Instagram, I appreciate that phone cameras have become a gateway that gets people interested in photography as a whole. The oft used phrase “the best camera is the one you have on you” is the absolute truth. When I need to capture something quickly, I pull out my phone. Though when I want to capture it well, I follow up with my DSLR later. I get excited when something arrives, and I want to talk about it. I snap a photo, drag into Lightroom Mobile—which is fantastic—to make some adjustments, and off it goes. My audience knows the real deal is coming later on, so it is a decent way for me to build anticipation for the main attraction.

Phones have gotten so good! What is wrong with them? I am asked. Noise. Detail. Composition. Lighting. Everything I love about photography, really. Computational photography is tuned for humans and landscapes. It has no idea what to do with things. What do I shoot mainly? Yeah, you see my point. My phone always wants to smooth this, sharpen that, and light the way it wants to. It does not care what I want. Sure, you can shoot some semblance of RAW photos, but you cannot remove all the computational side effects. In a pinch, I can produce a passable result, but I only use it for fleeting moments like unboxing something. When I want to truly express my subject, it waits until I get home.

A beautiful sunset, my new nephew cracking a smile, or an event unfolding before my eyes. I will always be glad to have my phone when that happens. I will always be happy when Tim Apple gets on stage and tells me all the wonderful things they can now do. I love technology and love to see it grow, but phone cameras and computational photography will continue to exist on a separate plane from where my creative passion exists.

High dollar DSLRs do not make better photographers

This is a statement that can be misinterpreted easily. Semantics are at the mercy of mindset. The most common question I get when sharing photos across social media is “what camera do you use?” I will not lie. The question used to bother me in the beginning. It felt immediately dismissive of my creativity and what I have worked for in capturing images. I liken it to crediting a racecar for victories, while paying no mind to the driver. You may win a short race with fast a car, but on a challenging course, the more skilled driver wins. With photography, there is so much that goes into releasing the shutter.

I started with a Canon Rebel XTi, and over the years have upgraded to a 5D, 5D Mark II, 5D Mark III, 5D Mark VI, EOS R, and now I have the EOS R5. I keep the last gen camera as my second shooter and sell off earlier models. My Canon EOS R5 was $3,899. My Canon RF 50mm f/1.2L USM lens was $2,299. Both items were staggeringly expensive, but I make enough in the field to justify the expense. That said, I can do with a lot less. My upgrades come as part of my passion for the technology in this hobby. I never replace a camera expecting the incoming camera to make me a better photographer. New bodies bring technical improvements (higher resolution, better low light performance), technological conveniences (Wi-Fi/autofocus), and overall, a renewed passion. They do not compose shots, teach you how to light a subject, or edit your photos for you. These are things you bring to the table.

In my collection, I have a Canon Rebel T2i. I paid less than $190 for the body, 18-55 EF-S kit lens, and 5 batteries. I mix this camera in from time to time (not when I am being paid) and it is fun to shoot with. Another aspect of fun it brings is when I reveal that that is what I was shooting with when someone asks. I enjoy showing people what can be done at every level. I have had the EOS M, EOS M3, EOS M50 as well. None as technically proficient as the full-frame bodies I mainly use, but still, lots of run when I need to pack lighter.

The major differences can be seen when you pixel-peep if you know what you are looking at. Most of my audience either cannot tell or does not care. The place I, as the photographer, feel the difference is in editing. Once you are used to larger, higher resolution sensors that are better in low light, it can be quite jarring working with images with a lot less information. Recovering from shadows is a lot less forgiving, and the noise catches up to you quickly. Other than that, you lose cropping and some large print ability, but it is not a change that could justify over $3,500 difference to someone else.

If you are looking to get into the hobby, do not be afraid of the used market. Do not be afraid to ask for advice. Getting set up to shoot is easier than ever and it is one the best creative outlets there is in terms of a learning curve.

Comments?

Leave us your opinion.